- Type I: for the most part the tonsils are herniated down into the cervical canal. We now know in some cases that part of the brain stem hangs down.

- Type II: is usually associated with meningomyelocele, a lot more changes usually and you’re going to recognize those that will have Type II at birth by seeing the sac, if you will, on the lower back usually.

- Type III: is very rare and it’s the herniation of the cerebellum into a fluid filled pocket at the back of your head and it’s just called a meningocele and this is under development of the cerebellum and mini investigators no longer include that into the typing of Chiari malformation.

And of course today we’re going to spend time obviously on Type I. One of the tests that’s really made a difference, a really dramatic difference, frankly, and as you know a few years ago the developers of MRI technology won the Nobel prize- is MRI and the way it allows us to look inside the nervous system. Even when I started in medicine we didn’t have that capability. And to think, at that time in the 70s, when I was in medical school that we’d be able to really look in– we were just starting with CT giving us crude images- – but to imagine that we could look in like we are today is really just unbelievable! It’s amazing the revolution that we live through, but the test that’s made a big difference of course is the MRI.

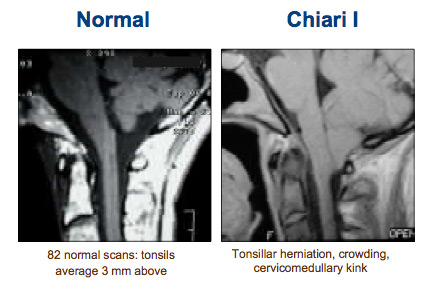

Figure 7

Here’s what we’d like to see normally, [see Figure 7] and that is a fluid filled pocket back in this area. You all recognize this anatomy. Here’s the bone and here’s the end of the bone here, this is the foramen magnum– nice space and spinal fluid’s going to be able to flow. Here, instead, what we’re seeing is the tonsils herniated and hanging down to cervical I and it’s causing this cervical medullary kink here at the bottom of the brain stem.

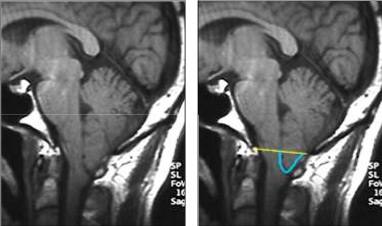

Figure 8

How do we assess Chiari? We can create a line at the foramen magnum and measure from that line the furthest point for the tonsils. And there’s some debate whether it needs to be 3mm hanging down, 5mm hanging down or whether we should rethink this altogether and define it in terms of flow and compression of these areas. But the bottom line is 3-5mm or more and most will agree that that’s the Chiari malformation. Here’s a young man, [see Figure 8] I think he’s in his mid 20s, he works at a nuclear power plant actually in Missouri and he inspects the crawl spaces with a lot of pipes. It’s about 4 foot high and they have to look at all these pipes periodically and actually what they do is x- ray them. And if he coughs, he rises up and hits his head and his helmet on the pipes because his head hurts so much to cough and that’s what brought him finally into the clinic. Of course, he was having a bad cough headache and his tonsils are herniated down. Here’s the kink in the brain in the cervical medullary junction, [see Figure 9]

Figure 9

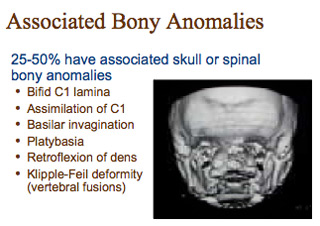

here’s the tonsils hanging down below the foramen magnum. Here, on an MRI that is, this is a T1 image where the spinal fluid is dark, this we call T2 where the spinal fluid is white, but it again shows you the blockage or obstruction at the foramen magnum where there shouldn’t be one. We have a variety of other ways to look at the MRI, not just a side view, but here’s a front view or coronal view and we can see that this tonsil is larger than that but they’re both stuffed down. We can do a cross section view through that area, these two cross section views, and see the crowding. So the MRI tells us a lot. CT scan also helps. Many people, 25-50% roughly, will have some kind of boney anomaly or boney change, an abnormality. There can be a variety of changes; they’re listed here, I won’t read through them. In this 3D CT [see Figure 10] scan we see this is the back of the skull, this is cervical II, cervical III and cervical I is actually fused up to the skull base so it’s a fusion anomaly in that area.

Figure 10