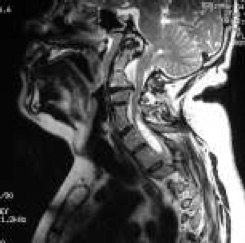

Figure 11

There can be other anomalies. This man with a blocked vertebra, two fused vertebra, here, [see Figure 11] this is called a Klippel Feil anomaly. He’s pinching his spinal cord here, he’s obstructing his foramen, he’s got a syrinx here, so these diagnostic tests can tell us a lot. OK, so we’re crowded in that area but still what does that mean? What does it mean to be crowded? One thing we have to keep in mind is that we, and this is from Dr.Milhorat’s classic work, are describing that the posterior fossa tends to be small in people with the Chiari malformation and maybe in that development we have hanging down of the tonsils. So shed insight into the fact that this area is small in comparison but we also know that the brain moves with each heartbeat and it moves a lot with each cough. So instead of sitting there peacefully in this container of spinal fluid it actually pulses, the brain enlarges, and as it enlarges, it runs into a fixed skull. So it has to move. It moves downward and these are from MRI studies analyzing the movement of the brain with each heart beat. And if you look at it on cross section, the movement radiates out, radiates somewhat posteriorly, but these views show us that the movement tends to be down. Now what about if you’re crowded in this area here and you cough and sneeze? That may block the spinal fluid flow obviously.

Figure 12

And then it’s this blockage that results in syringomyelia ( it’s debated right now as to how the fluid gets into the spinal cord, although we’ll probably hear about it later on in this meeting and get some more insight). So here now on MRI is what Chiari described in his second paper in the late 1800s. And this syringomyelia can look quite different on each individual. [see Figure 12] Here’s one that she seems to have multiple dilatations et cetera, this is thin, there’s another part of the syrinx, there’s a large syrinx extending from the cervical down into the thoracic. This is an individual without a cervical syrinx but one in the thoracic area, so it can look quite different.

So that’s the anatomy and the diagnostic MRI work up at least. But what are the common symptoms? We studied our first 100 patients (and by we I mean myself and Dr. Diane Meuller) and we found that the most common was the headache. It’s fairly characteristic, not always, but it’s different from migraine, it’s different from tension headache. It’s often suboccipital in the back of your head, it tends to radiate forward. We found radiating behind the eyes is more common, maybe just on one side although it can radiate to the top of the head, the side of the head. And it’s described in a variety of different ways but when it’s severe people will often say ‘it’s a severe pressure in my neck and head, it feels like my head will explode, like someone is blowing a balloon up in my head or like my head will pop off.’ That’s not a migraine type of headache, that’s not a tension type of headache. The headache most often, although not always, is worse with valsalva activities, these are where you tense your thoracic spine, increase the pressure in your veins in your chest and abdomen and therefore the venous blood out of your brain is not draining as well so you’ve got more blood in your brain. Then if you cough you’re going to have that pulsatile expansion of your brain and it’s going to move down and your headache will be severe. So, again, this is what we call a valsalva related type of headache. Basically you can imagine stuffing this area tighter and then the spinal fluid is not able to get out of the head and get into the spinal cord.