Figure 16

Moving on, there can be, of course, heart, respiratory and vascular symptoms and we’ve certainly had complaints of abdominal symptoms as well. The bottom line for many people over time is life becomes miserable. All these different problems start adding up. The problem in this disorder is that those symptoms that I’ve listed for you can be caused by a large number of other disorders and this is only a partial list, you can take a look at it yourself. But that’s the difficulty for the physician and that’s where we need more progress, diagnostic tests. Just because we see a Chiari malformation, is it truly the cause of this individual’s symptoms? That is not easy to determine and it takes a work- up. It takes other colleagues to help sort out these other conditions and again I really want to emphasize this point that just because there’s a hang down of the tonsils it may not mean, or it may be that you still have some other problem.

[see Figure 16] Variety of non-operative treatments for the Chiari malformation, we’ll probably hear more about them during this meeting, but certainly if the symptoms are mild and nonprogressive, you want to help your patient improve without surgical therapy. Even if they are progressive and severe you still want to try to help them with nonsurgical treatments. I’ve had some patients be helped very well with migraine medications or other medications or treatments. However if the symptoms become progressive and relenting, and no other cause can be determined then surgical treatment can be an option.

Figure 17

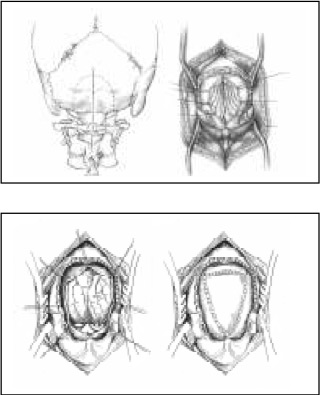

Let me just briefly review our approach. I don’t think it’s too different from most of the specialists here. Most people are placed in a face down position; [see Figure 17] this is the amount of hair I usually shave. My incision’s a little longer at the upper area then some because this is where the graft will come from once everything gets draped out. The procedure is a fairly standard. [see Figure 18]

Figure 18

I use about a 3×3 cm craniectomy and a cervical laminectomy. This is the lamina of cervical 1 and it’s resected at the edges, the joint is here and here, and there’s a joint up front so we’re not affecting the joints. This is the bony removal. This is the membrane, the dura membrane, and it’s opened in a Y shaped fashion ( a Y type of incision) the tonsils are seen. It’s not time to debate whether to shrink the tonsils or not but those are judgments that all the surgeons have to make. The bottom line is we want to expand this area and we do it with a patch graft. [see Figure 18] Now again, I take the patch graft from the patients own tissue and I’ll show that in a minute.

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

This is like we’d like to do (here’s a side illustration) and enlarge that area. Here’s an actual procedure, if you will. [see Figure 19] This is opening the lower part of the incision. The upper part for the graft will be here. [see Figure 20] This is the bone at the base of the skull, measured and marked out, this is first cervical. Now most of us do this by using a high speed drill to core out the bone to a thin shell which then is removed with a biting instrument. You can see [see Figure 21] how thick the bone was down low, this will be the foramen. It’s hard to see cervical 1 but its right there.

Figure 22

Figure 23

Now the bone has been removed, [see Figure 22] this is the dura membrane, and the edge of C1 is here, and I think somewhere about there. Now this will need to be opened: I’m showing harvesting the graft, [see Figure 23] which is a lining on your skull underneath the scalp, this is your tissue, your own tissue. This is what the surgery view may look like. [see Figure 22] It may be the tonsils are hanging down but look pretty good, it may be that they’re fibrous, adherent, scarred down and not looking so good. So it depends on what you’ll see.