APR 11, 2024

By David Pedersen

APR 11, 2024

By David Pedersen

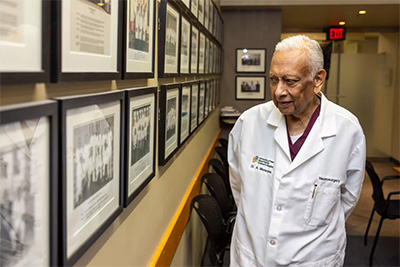

Neurosurgeon recognized worldwide as pioneer in treating skull-base abnormalities

What defines a legend?

What defines a legend?

While the term is often applied to individuals who achieve even a modest level of success, a true legend transcends their accomplishments and awards. They challenge the status quo, upend preconceived notions and stereotypes, and change lives through their ideas and their actions.

Arnold Menezes, MBBS, is a legend.

In 2024, the world-renowned neurosurgeon and clinician marks 50 years of service at the University of Iowa. Since completing fellowship training in pediatric neurosurgery at Iowa and joining the university’s medical faculty in 1974, Menezes has transformed understanding and surgical approaches of the craniocervical junction—the area where the skull meets the spine.

Menezes has treated thousands of patients throughout his career from across America and around the world. Since the 1970s, he has designed neurosurgical procedures at the base of the skull, and he’s built one of the world’s largest databases that tracks disorders of the craniocervical region.

He has authored hundreds of peer-reviewed publications, written foundational textbooks on craniovertebral abnormalities, and delivered well over 800 scientific presentations throughout the U.S. and abroad. He was involved in developing some of the first practical courses in spine surgery, and he was instrumental in establishing spinal neurosurgery programs in Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America.

Through it all, he has trained, mentored, and influenced hundreds of resident physicians, colleagues, and staff—serving as role model for excellence and enthusiasm in neurosurgery and academic medicine.

“Within our specialty, everyone—and I mean neurosurgeons around the world—views Arnold as the premier guy in this particular area of research and treatment,” says Matthew Howard, MD, professor and chair of the UI Department of Neurosurgery. “That’s why so many colleagues from all over the world refer their patients to Iowa. He was able to identify and correct these problems at the juncture of the skull and spine. He’d figure out how each patient should be treated, then he’d spectacularly attend to every detail in the O.R. and in clinic. Every detail, he was on top of it.”

When asked to reflect upon his years at Iowa, Menezes cites a collaborative culture that allowed him to learn and develop his expertise. He also acknowledges the pressure he placed on himself to succeed.

When asked to reflect upon his years at Iowa, Menezes cites a collaborative culture that allowed him to learn and develop his expertise. He also acknowledges the pressure he placed on himself to succeed.

“Being foreign-born, I felt I needed to prove myself—not just here, but anywhere. But once you are accepted, you are part of everything,” he says. “When I came here as a resident, there were few, if any, people of Indian origin in the medical school. If you walk around the hospital today, you’ll see people working here from all different backgrounds. That’s good.”

Howard, who has worked with Menezes for more than 30 years, still marvels at his colleague’s resilience.

“Here’s a guy who wasn’t being given a lot of opportunities coming out of medical school, and yet he found opportunity at the University of Iowa. That says a lot about this place,” Howard says. “He identified a terrible, unsolved problem, and he dedicated himself to understanding and fixing it. And he’s still getting after it. He’s just the toughest nut I’ve ever seen.”