The Chiari I Abnormality in Childhood

The Chiari I Abnormality in Childhood

The Chiari I Abnormality in Childhood

by Arnold H. Menezes, MD

The following article is a transcribed presentation from the 2004 ASAP Conference.

Abstract

The clinically symptomatic child with the hindbrain herniation syndrome (Chiari I) can differ significantly from the adult patient. A prospective analysis of these children has brought an understanding of the various presentations

.

The primary symptoms below age 5 have been failure to thrive secondary to repeated aspirations, gastroesophageal reflux and headaches. Between ages 3-10 years, headaches and scoliosis were the main symptoms together with neurological abnormalities secondary to the cerebellar tonsillar impaction and syringohydromyelia.

The factors affecting treatment have been clinical symptoms/signs, posterior fossa volume, craniovertebral junction abnormalities and instability. Taken together, these substrates provide for successful outcome.

Transcribed Presentation Notes

But why should it happen in the very young, before the skull has fully formed and developed? And is there any way in which we can predict or help these children who come in with different forms of presentation? So in light of that, we reviewed– this is a prospective study thats been going on for many years– we reviewed our series and we thought wed focus on childhood.

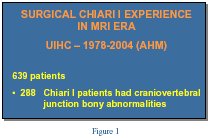

Ive been at the University of Iowa since 1969 [see Figure 1] and my interest in terms of keeping a detailed log started out fairly early. We have a prospective data base and it looked at nearly 600 surgical patients, because of my interest in abnormalities of the skull base, bony abnormalities, about 2/5 of them, nearly half of them, were patients who had problems with skull base abnormalities. But when we focused on children below the age of 6 years, [see Figure 2] we thought that our reason for doing this would be, how did this defer in terms of presentation from the adults or anybody above that age? And why did we pick the age of 6? Because it begins to be statistically significantly. We wanted to achieve an early diagnosis, and more importantly, we need to educate medical practioners, such as pediatricians, family practioners, general practice, neurosurgeons too, and I think that that was something we needed to achieve. Once we came to some conclusions, we thought that our best bet was to have special meetings, instead of going ahead and presenting this at neurosurgical national meetings, which is what we do, but also to educate the pediatricians. The Journal of Pediatrics has a circulation of over 300,000 and its translated into 4 languages and goes out world wide.

If they strain then theyre going to increase their headache, so they become further constipated, its a vicious cycle. The next thing that happens is there is a hard stool that is coming through and they get a fissure that makes it more painful, so they scream before in anticipation both of the headache as well as now for the rectal fissure problem.

So headache was one, the next was repeated aspiration and pneumonia. Ill explain to you what repeated aspiration means. That means things going down the wind pipe, both liquid and solid but most of the time its liquid because in the food pipe, the pharynx has a chance to grab onto food, it can propel it down, but liquid (now Im not talking about yogurt or soft ice cream, Im talking with straight liquid) the pharynx doesnt have a chance to grab onto it, so it can go the wrong way.

Sleep apnea, you all know what sleep apnea is, meaning, you know there was a term that was used a long time ago called ondines curse and that was the curse of a woman whose lover jilted her and left for somebody else. She said that “when you sleep with somebody else youll fall asleep and you wont wake up, youll stop breathing.”

Weakness and gait abnormalities. Now remember a child starts walking, starts cruising around at about 10 or 11 months of age and becomes steady on the feet only at about 2 years of age. They walk like they are on a boat, wide stance and then they are toddling around; we have to go past that normal phenomenon. Were talking about true gait abnormalities, a child who has already achieved independent walking and then has difficulty again; so a backward step.

Failure to thrive. Scoliosis is in about a third of the patients and then developmental delay because youve got nutritional factors that come in.

When we examined them [see Figure 5] we looked for oralpharyngeal abnormalities. We talked about aspiration, difficulty swallowing, regurgitation, meaning coming up the wrong way. Now its a very common diagnosis in pediatrics to have what is called achalasia cardia. That means the sphincter that closes off between the stomach and the esophagus down about here, should close off after youre finished eating. In 40% of children, especially males, below the age of 2, they can regurgitate and you know that you always put an apron or a towel or a bib around the child after feeding them because it comes up. This is a little different and it comes up with a big projectile movement.

Vocal cord dysfunction. Your vocal cord and mine is innervated by the tenth nerve that keeps it moving in and out. When were breathing it opens up, when were swallowing it closes down. If instead theres an abnormality and its going to stay partly open, it can allow food to go through. Second thing is that if you watch a child and if you hear the (strider sound) that means that things are not going right- its in a bad position. Choking and chronic cough occur because things are going the wrong way. Gait and motor impairment, sometimes sensory. Kids cant tell us that theyre having sensory abnormalities but what they do is they start rubbing their hands or they dont want somebody to touch them.

Scoliosis. No exam is complete without scoliosis.

I broke this down to be very simple, [see Figure 6] just to see that swallowing and oralpharyngeal dysfunction is significant. 16 out of 24, as opposed to 2 out of 21. So kids come in with this problem earlier, the older child comes in with scoliosis and headache, theyre more able to tell us what the problem is. And a syrinx was less common, a cavity in the spinal column was less common, below the age of 3, then between 3 and 6. So to sum up the slide, weve got more of a problem below the age of 3.

In our institution when we are considering an operative procedure on anybody with this situation we look at the clinical presentation. We like to see the anatomy, we do many studies, some of them are volumetric analysis to tell us the size of the area. We check this out with 3D CTs, MR. The important is stability. Is this area rocking? Does the position change between the head tipped back / extension / flexion or sideways? How do we assess that? With an MRI usually.

Is there hydrocephalus or is there a syrinx? And since we see a lot of kids we talk about other things that are going on, such as, bony abnormalities, and theyre called a skeletal dysplasia.

Of these children all 45 had an operation from behind. [see Figure 7] 5 of those 45 had a problem from in front that required attention from in front and from behind too. Posterior fusion was needed in 3 of the 45 below the age of 6. Now everyone whos had an anterior procedure and the other too patients requires a posterior fixation. Weve talked about this since 1980 and its more or less accepted. When I first came to this meeting talking about these Chiari problems I made a mistake that all of us do, we forget that we are not at a medical neurosurgical convention and we showed pictures that made

some in attendance uncomfortable.

This is through the microscope, [see Figure 9] shows you the tonsils are down, this is the left side, the right side, and its squeezed down. We shrink them, make them go up or move them so that the opening through the cavity in the brain, the 4th ventricle is still exposed, [see Figure 10] and then we finish it off making sure that everything is wide open and satisfactory and keep it in place. And the analogy I give my patients and parents, if I have a waist of 38 and I have a belt of 34 Im in trouble, so either I get a new belt or I splice a new patch [see Figure 11] which means that I have to increase it to 40 so that I can breath which is exactly what she is doing, which is called a dural graft.

This is through the microscope, [see Figure 9] shows you the tonsils are down, this is the left side, the right side, and its squeezed down. We shrink them, make them go up or move them so that the opening through the cavity in the brain, the 4th ventricle is still exposed, [see Figure 10] and then we finish it off making sure that everything is wide open and satisfactory and keep it in place. And the analogy I give my patients and parents, if I have a waist of 38 and I have a belt of 34 Im in trouble, so either I get a new belt or I splice a new patch [see Figure 11] which means that I have to increase it to 40 so that I can breath which is exactly what she is doing, which is called a dural graft.

So thats one side of it. [see Figure 12] But what about this patient such as this young man who is 6 years old? He has an abnormality; this is the space here through which the brain should come down into the spine. Well, half of that is taken up with this bone that is projecting into it, thats called basilar, and there is an abnormality here because the second bone is stuck to the third front and back and its pushed up. This should have been right here. Can we avoid 2 operations? Thats the important thing that means going from in front -big procedure, through the mouth; taking this out, going from behind, try to make it only one operation. So what we do is we try and get this patient into traction and pull it down. The 3D CT, this is just to show you the hologram of 3D rendition of the problem. It shows you that things have abnormal alignment. Youre looking at the spine and skull just as though youre holding it in your hand from in front. In traction we were able to pull that bone which was up here down so that the space here is correct and we could get by with an operation only from behind.

So thats one side of it. [see Figure 12] But what about this patient such as this young man who is 6 years old? He has an abnormality; this is the space here through which the brain should come down into the spine. Well, half of that is taken up with this bone that is projecting into it, thats called basilar, and there is an abnormality here because the second bone is stuck to the third front and back and its pushed up. This should have been right here. Can we avoid 2 operations? Thats the important thing that means going from in front -big procedure, through the mouth; taking this out, going from behind, try to make it only one operation. So what we do is we try and get this patient into traction and pull it down. The 3D CT, this is just to show you the hologram of 3D rendition of the problem. It shows you that things have abnormal alignment. Youre looking at the spine and skull just as though youre holding it in your hand from in front. In traction we were able to pull that bone which was up here down so that the space here is correct and we could get by with an operation only from behind.

This is a child who stopped dancing because every time she did a cartwheel or a flip she got into trouble. This MRI shows that shes got this portion of her cerebellum hanging down and the area looks pretty abnormal. [see Figure 13] This should have been a nice curve down here, instead its dented backwards. So instead of having a convexity forward shes got a concavity– that means weve got a problem in front. And this is what we talk about flexion/extension MRIs. We get an MRI, a control study and we are seeing that this dent here, [see Figure 14] focus on this, that dent needs to go, either with an operation, or position, or traction. In addition weve found that if this dent has this blood vessel over it and bangs against it, 25% of these children come in with headaches, and with the older patients its called migraines. Why does that happen? Because that blood vessel gets banged against, you stop it, put them in traction or fuse them, and it is relieved.

What we showed was that if they are operated on, early on, below the age of 12, that 80-90% of them by 12 (were talking about puberty) crossing over, growth spurt and changes in the bony configurations, that this can be handled earlier and get by without doing a scoliosis operation. Can we prove it? Theres a child that comes in with this big combination, [see Figure 17] weve got a portion hanging down here, the cavity in the spinal cord, this is accompanied by not a bad scoliosis but about a 20 angulation. This is the post-op MRI. [see Figure 18]

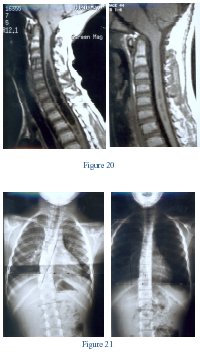

Somebody that I look up to, Peter Carmel, described this very early, 1972. This is something I always look at, and if I see it there then I know Ive got a very big problem. Dr. Milhorat has described this too. But heres a big cavity in the spinal cord. Thats post op, [see Figure 20] things look good, thats the scoliosis [see Figure 21] before the procedure, thats within 6 months. I am very fortunate to be associated with a pediatric orthopedist, Dr. Weinstein, and hopefully we can get him to talk at the meeting next year. Dr. Weinstein sees about 1500 kids a year and performs something like 200 scoliosis operations. Dr. Weinstein sees the scoliosis and if theres anything abnormal they automatically all get MRIs and then I take care of them and then he follows through to make sure things have gotten well. He was co-author in some of this material and what youre seeing here, has changed orthopedic thinking. We put these kids in a brace to see if thats going to take care of it and over a period of 6 months we had an improvement. Not everybody does, but Ill figure sure about 86% of them will get better. Im talking about our whole series of scoliosis.

Somebody that I look up to, Peter Carmel, described this very early, 1972. This is something I always look at, and if I see it there then I know Ive got a very big problem. Dr. Milhorat has described this too. But heres a big cavity in the spinal cord. Thats post op, [see Figure 20] things look good, thats the scoliosis [see Figure 21] before the procedure, thats within 6 months. I am very fortunate to be associated with a pediatric orthopedist, Dr. Weinstein, and hopefully we can get him to talk at the meeting next year. Dr. Weinstein sees about 1500 kids a year and performs something like 200 scoliosis operations. Dr. Weinstein sees the scoliosis and if theres anything abnormal they automatically all get MRIs and then I take care of them and then he follows through to make sure things have gotten well. He was co-author in some of this material and what youre seeing here, has changed orthopedic thinking. We put these kids in a brace to see if thats going to take care of it and over a period of 6 months we had an improvement. Not everybody does, but Ill figure sure about 86% of them will get better. Im talking about our whole series of scoliosis.

“why?” And it still is. Go back to the root cause, something hasnt gone right. Could be the scarring, reformation of bone, or something else might have happened or they became unstable and we found that if you went back youd be able to correct the situation in 2 out of those 4. My usual line up is that if I’m given 30 minutes to talk I’ll try to take only 20 minutes to give you chances if you have any burning questions.

Thank you.