Current Synthesis

Current Synthesis

by John J. Oró, MD

Abstract

In papers published in 1891 and 1894, pathologist Dr. Hans von Chiari described a series of hindbrain malformations now known as the Chiari malformations. The traditional definitions went unchallenged for over 100 years. However, the marked advances in medicine over the past couple of decades have led to a new understanding of these malformations and proposed new definitions. We will review the pertinent neuroanatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of patients with CMI with or without syringomyelia. Emphasis will be placed on new research findings, new concepts, and the current naming controversy.

Transcribed Presentation Notes

Figure 1

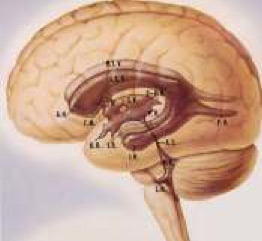

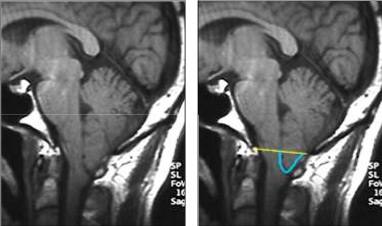

Well thank you, it’s always a great pleasure to be here annually at this meeting. We’re going to talk about the Chiari Malformation and syringomyelia. To get started we have to have a sense of the normal anatomy. Let’s start with the ventricular system here[see Figure 1].

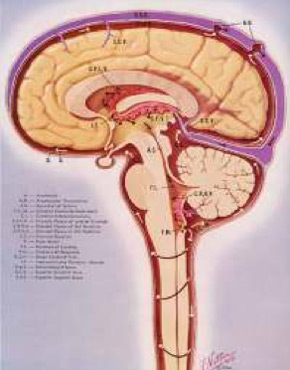

Within the core of the brain there are fluid spaces called the ventricles and it is in these ventricles that spinal fluid is created and it has to flow a certain direction. These large two ventricles up here connect to this small little canal, into a third ventricle, down the Aqueduct of Sylvius, into the forth ventricle and then they drain out through three openings into the spaces on the outside of the brain and around the spinal canal. Here we have a cross sectional image [see Figure 2] showing the inside of the ventricles. This is the choroid plexus- it’s a tuft of vascular tissue.

Figure 2

With each pulsation an ultra filtrate is created of spinal fluid that again has to flow down these pathways into the forth ventricle and comes out- in particular in this foramen (opening) of Magendie, and two on the side; and here we have a cistern. This fluid filled space, is the cisterna magna, which we’ll talk some more about. It flows around the spinal canal on up and it has to find it’s way for the most part up into this area where it – through these little granulations as they’re called – gets backed into the venous system, and this happens with every heart beat, about 100,000 times a day.

Figure 3

The area that we’re going to talk about today, which is this posterior fossa, this compartment down low here where we see the brain stem turning into the spinal cord and we see the cerebellum in this area. The posterior fossa: there is a lot of activity in the area. The cranial nerves, the nerves that run the eye movements, the facial movements, the tongue movements, et cetera, come out of the brain through the brain stem in this area here. Regulatory mechanisms for the heart and the lungs are in this area, and of course, the cerebellum, and all the highways coming up and down the spinal cord are traveling through this area. So it’s a very busy area. From our point of view, as far as the Chiari malformation is concerned, this is some anatomy [see Figure 3] that we want to kind of put into our brains, if you will, to help understand things. This is a side view of the posterior fossa and what you’re seeing here is some bone at the base of the skull and in the back of your skull, ending at this point, called the basion. This point is called the episthion, and that’s not that important, but the bottom line is the opening at the base of the skull. A line drawn from here to here (and it happens to be called the foramen, which we know is anopening) the foramen magnum (and magnum means large) the large foramen at the base of the skull. Normally what you’re supposed to have in this area is a cistern, a fluid pocket, if you will, and it’s large and when the ancients found this they gave it the term magna, again for large, so it’s the cisterna magna.

Figure 4

And this is a happy situation with the brain stem turning into the spinal cord, the cerebellum. It helps us to look from behind to see that there are two tonsils. [see Figure 4] This is the cerebellum and the protrusions at the bottom of the cerebellum are called tonsils, different from the tonsils at the back of our throat, of course. They hang down to the foramen. Here’s the spinal cord, these are the vertebral arteries that supply the brain, two of them that supply the brain, here’s an important branch of this vertebral artery called posterior inferior cerebellar artery or PICA for short, that supplies the brain stem itself and obviously is a very critical blood vessel. Just a little bit on spinal cord anatomy. [see Figure 5] Spinal cord is a complex highway track. There are highways running up and down and the big highways, in particular, the lateral cortical spinal track, this is heading down and helping you move your arms and legs. It’s of interest that the fibers coming out of the neck are closer to the center of the cord. These are feeling fibers. Also of interest that the cervical is more central than the sacral, this is thoracic, lumbar, sacral. And some other, but the bottom line is that when we’re going to talk syringomyelia it’s going to occur here centrally and it may start impacting some of these fibers earlier than the later fibers. A little bit of anatomy, but it’s also important to recognize the history.

Figure 5

Figure 6

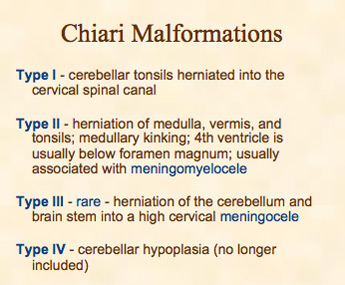

It was Charles Prosper Ollivier d’Angers, a French pathologist, who in 1827 wrote this treaty on the spinal cord and its illnesses here in French and this is where he created the term syringomyelia. He had found a cavity within the spinal cord of some of his dissections and he created this name from Greek. Syrinx, meaning a pipe or tube or channel and myelus, the word for marrows. So a syrinx in the marrow, or syringomyelia is where we get the first name for syringomyelia. And then of course, Dr. Chiari, somewhat later in that century, wrote two very important papers. He’s the professor at the University of Prague, a pathologist. He wrote a paper concerning the changes in the cerebellum due to hydrocephalus of the cerebrum. And it is in this paper he described three types of brain stem anomaly of the hindbrain and gave a case for each. But he kept working and a few years later reported on another 24 cases and this is the first report showing that syringomyelia could occur in people with Chiari malformations, so it’s the first association now of those two conditions. And so what are the types to review? [see Figure 6] Initially he described 4, at least by a second paper he described 4.

- Type I: for the most part the tonsils are herniated down into the cervical canal. We now know in some cases that part of the brain stem hangs down.

- Type II: is usually associated with meningomyelocele, a lot more changes usually and you’re going to recognize those that will have Type II at birth by seeing the sac, if you will, on the lower back usually.

- Type III: is very rare and it’s the herniation of the cerebellum into a fluid filled pocket at the back of your head and it’s just called a meningocele and this is under development of the cerebellum and mini investigators no longer include that into the typing of Chiari malformation.

And of course today we’re going to spend time obviously on Type I. One of the tests that’s really made a difference, a really dramatic difference, frankly, and as you know a few years ago the developers of MRI technology won the Nobel prize- is MRI and the way it allows us to look inside the nervous system. Even when I started in medicine we didn’t have that capability. And to think, at that time in the 70s, when I was in medical school that we’d be able to really look in– we were just starting with CT giving us crude images- – but to imagine that we could look in like we are today is really just unbelievable! It’s amazing the revolution that we live through, but the test that’s made a big difference of course is the MRI.

Figure 7

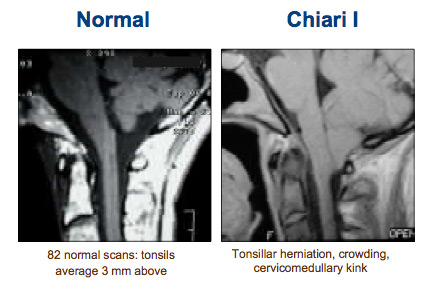

Here’s what we’d like to see normally, [see Figure 7] and that is a fluid filled pocket back in this area. You all recognize this anatomy. Here’s the bone and here’s the end of the bone here, this is the foramen magnum– nice space and spinal fluid’s going to be able to flow. Here, instead, what we’re seeing is the tonsils herniated and hanging down to cervical I and it’s causing this cervical medullary kink here at the bottom of the brain stem.

Figure 8

How do we assess Chiari? We can create a line at the foramen magnum and measure from that line the furthest point for the tonsils. And there’s some debate whether it needs to be 3mm hanging down, 5mm hanging down or whether we should rethink this altogether and define it in terms of flow and compression of these areas. But the bottom line is 3-5mm or more and most will agree that that’s the Chiari malformation. Here’s a young man, [see Figure 8] I think he’s in his mid 20s, he works at a nuclear power plant actually in Missouri and he inspects the crawl spaces with a lot of pipes. It’s about 4 foot high and they have to look at all these pipes periodically and actually what they do is x- ray them. And if he coughs, he rises up and hits his head and his helmet on the pipes because his head hurts so much to cough and that’s what brought him finally into the clinic. Of course, he was having a bad cough headache and his tonsils are herniated down. Here’s the kink in the brain in the cervical medullary junction, [see Figure 9]

Figure 9

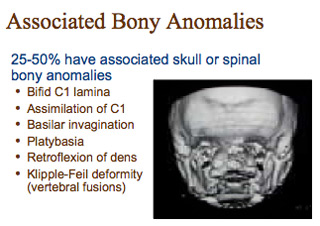

here’s the tonsils hanging down below the foramen magnum. Here, on an MRI that is, this is a T1 image where the spinal fluid is dark, this we call T2 where the spinal fluid is white, but it again shows you the blockage or obstruction at the foramen magnum where there shouldn’t be one. We have a variety of other ways to look at the MRI, not just a side view, but here’s a front view or coronal view and we can see that this tonsil is larger than that but they’re both stuffed down. We can do a cross section view through that area, these two cross section views, and see the crowding. So the MRI tells us a lot. CT scan also helps. Many people, 25-50% roughly, will have some kind of boney anomaly or boney change, an abnormality. There can be a variety of changes; they’re listed here, I won’t read through them. In this 3D CT [see Figure 10] scan we see this is the back of the skull, this is cervical II, cervical III and cervical I is actually fused up to the skull base so it’s a fusion anomaly in that area.

Figure 10

Figure 11

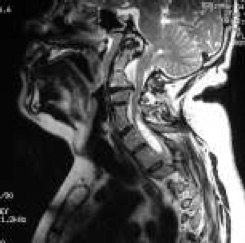

There can be other anomalies. This man with a blocked vertebra, two fused vertebra, here, [see Figure 11] this is called a Klippel Feil anomaly. He’s pinching his spinal cord here, he’s obstructing his foramen, he’s got a syrinx here, so these diagnostic tests can tell us a lot. OK, so we’re crowded in that area but still what does that mean? What does it mean to be crowded? One thing we have to keep in mind is that we, and this is from Dr.Milhorat’s classic work, are describing that the posterior fossa tends to be small in people with the Chiari malformation and maybe in that development we have hanging down of the tonsils. So shed insight into the fact that this area is small in comparison but we also know that the brain moves with each heartbeat and it moves a lot with each cough. So instead of sitting there peacefully in this container of spinal fluid it actually pulses, the brain enlarges, and as it enlarges, it runs into a fixed skull. So it has to move. It moves downward and these are from MRI studies analyzing the movement of the brain with each heart beat. And if you look at it on cross section, the movement radiates out, radiates somewhat posteriorly, but these views show us that the movement tends to be down. Now what about if you’re crowded in this area here and you cough and sneeze? That may block the spinal fluid flow obviously.

Figure 12

And then it’s this blockage that results in syringomyelia ( it’s debated right now as to how the fluid gets into the spinal cord, although we’ll probably hear about it later on in this meeting and get some more insight). So here now on MRI is what Chiari described in his second paper in the late 1800s. And this syringomyelia can look quite different on each individual. [see Figure 12] Here’s one that she seems to have multiple dilatations et cetera, this is thin, there’s another part of the syrinx, there’s a large syrinx extending from the cervical down into the thoracic. This is an individual without a cervical syrinx but one in the thoracic area, so it can look quite different.

So that’s the anatomy and the diagnostic MRI work up at least. But what are the common symptoms? We studied our first 100 patients (and by we I mean myself and Dr. Diane Meuller) and we found that the most common was the headache. It’s fairly characteristic, not always, but it’s different from migraine, it’s different from tension headache. It’s often suboccipital in the back of your head, it tends to radiate forward. We found radiating behind the eyes is more common, maybe just on one side although it can radiate to the top of the head, the side of the head. And it’s described in a variety of different ways but when it’s severe people will often say ‘it’s a severe pressure in my neck and head, it feels like my head will explode, like someone is blowing a balloon up in my head or like my head will pop off.’ That’s not a migraine type of headache, that’s not a tension type of headache. The headache most often, although not always, is worse with valsalva activities, these are where you tense your thoracic spine, increase the pressure in your veins in your chest and abdomen and therefore the venous blood out of your brain is not draining as well so you’ve got more blood in your brain. Then if you cough you’re going to have that pulsatile expansion of your brain and it’s going to move down and your headache will be severe. So, again, this is what we call a valsalva related type of headache. Basically you can imagine stuffing this area tighter and then the spinal fluid is not able to get out of the head and get into the spinal cord.

Figure 13

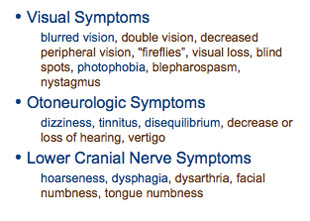

Again, by coughing my brain is going to expand because of the increased venous blood that’s in there so it’s going to quickly get a little larger, and water’s incompressible. So water has to go somewhere. It’s going to run up against the skull so it can only go one way for the most part, it goes down. And if the brain is moving down that way to block off all the outflow, all of a sudden that extra spinal fluid is going to be retained in the head. If you have a cisterna magna and you do that, fine– brain will expand, spinal fluid goes down into the spinal canal. The spinal canal, because it has a lot of veins on the outside and can actually expand a little bit, takes off the pressure like a relief valve and people without Chiari won’t notice much with a cough or a sneeze or a strain. So that’s the difference. But again, there’s a lot happening in this area and so we can see a variety of other symptoms. [see Figure 13] Visual symptoms are very common, in our case, blurred vision and photophobia, which means they don’t like bright lights. Hearing symptoms, dizziness, vertigo, balance, problems with the nerves at the very bottom, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing and a whole list. [see Figure 14]

Figure 14

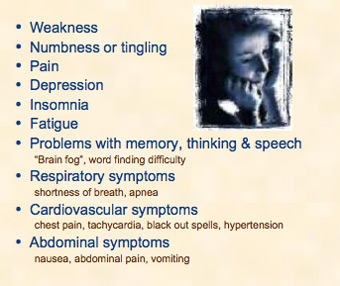

Weaknesses: the tracts are affected going down into the arms and legs. As the sensory tracts going up are affected, numbness and tingling can occur. There can be pain because that dura, the membrane around that area, has pain fibers in it. Then there are a variety of things that are associated with other disorders as well, certainly, as you can see here. [see Figure 15]

Fatigue is not unusual in this condition. Problems with memory and thinking: when we started hearing the term brain fog, I sort of discounted that thinking, how can that area be involved with memory and thinking? But indeed it’s not uncommon for people to describe difficulty in thought processes. I had a man who was sick and had repetitive bouts of coughing. After a spell of coughing he felt he had to get his thoughts back out through that fog, his thoughts were just not quite there. I visited with a neuropyschiatrist in the Denver area who tells me in their field the cognitive role of the cerebellum is being increasing looked at. In other words we used to just view the cerebellum as a coordination organ, if you will, but it may have a little more to do with some general cognitive function, although again that’s very preliminary and I hesitate to emphasize that too strongly.

Figure 16

Moving on, there can be, of course, heart, respiratory and vascular symptoms and we’ve certainly had complaints of abdominal symptoms as well. The bottom line for many people over time is life becomes miserable. All these different problems start adding up. The problem in this disorder is that those symptoms that I’ve listed for you can be caused by a large number of other disorders and this is only a partial list, you can take a look at it yourself. But that’s the difficulty for the physician and that’s where we need more progress, diagnostic tests. Just because we see a Chiari malformation, is it truly the cause of this individual’s symptoms? That is not easy to determine and it takes a work- up. It takes other colleagues to help sort out these other conditions and again I really want to emphasize this point that just because there’s a hang down of the tonsils it may not mean, or it may be that you still have some other problem.

[see Figure 16] Variety of non-operative treatments for the Chiari malformation, we’ll probably hear more about them during this meeting, but certainly if the symptoms are mild and nonprogressive, you want to help your patient improve without surgical therapy. Even if they are progressive and severe you still want to try to help them with nonsurgical treatments. I’ve had some patients be helped very well with migraine medications or other medications or treatments. However if the symptoms become progressive and relenting, and no other cause can be determined then surgical treatment can be an option.

Figure 17

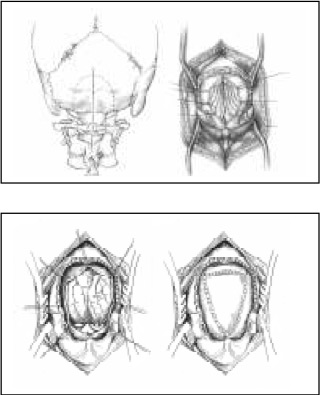

Let me just briefly review our approach. I don’t think it’s too different from most of the specialists here. Most people are placed in a face down position; [see Figure 17] this is the amount of hair I usually shave. My incision’s a little longer at the upper area then some because this is where the graft will come from once everything gets draped out. The procedure is a fairly standard. [see Figure 18]

Figure 18

I use about a 3×3 cm craniectomy and a cervical laminectomy. This is the lamina of cervical 1 and it’s resected at the edges, the joint is here and here, and there’s a joint up front so we’re not affecting the joints. This is the bony removal. This is the membrane, the dura membrane, and it’s opened in a Y shaped fashion ( a Y type of incision) the tonsils are seen. It’s not time to debate whether to shrink the tonsils or not but those are judgments that all the surgeons have to make. The bottom line is we want to expand this area and we do it with a patch graft. [see Figure 18] Now again, I take the patch graft from the patients own tissue and I’ll show that in a minute.

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

This is like we’d like to do (here’s a side illustration) and enlarge that area. Here’s an actual procedure, if you will. [see Figure 19] This is opening the lower part of the incision. The upper part for the graft will be here. [see Figure 20] This is the bone at the base of the skull, measured and marked out, this is first cervical. Now most of us do this by using a high speed drill to core out the bone to a thin shell which then is removed with a biting instrument. You can see [see Figure 21] how thick the bone was down low, this will be the foramen. It’s hard to see cervical 1 but its right there.

Figure 22

Figure 23

Now the bone has been removed, [see Figure 22] this is the dura membrane, and the edge of C1 is here, and I think somewhere about there. Now this will need to be opened: I’m showing harvesting the graft, [see Figure 23] which is a lining on your skull underneath the scalp, this is your tissue, your own tissue. This is what the surgery view may look like. [see Figure 22] It may be the tonsils are hanging down but look pretty good, it may be that they’re fibrous, adherent, scarred down and not looking so good. So it depends on what you’ll see.

Figure 24

You’d like to see a post operative picture somewhat like that. [see Figure 24] At least in our hands, that’s the procedure.

With any surgery there are always some risks. There’s a risk of leaking spinal fluid beyond the graft where you’re sewing in a water bag, basically. You can always have a risk of wound infection, meningitis, pain at the occipital nerves which run off to the side in the back of your head. The worst thing obviously would be a neurological deficit or stroke. And there are some other general medical risks to the surgery, so we have to keep those in mind and let me briefly run through just a few cases.

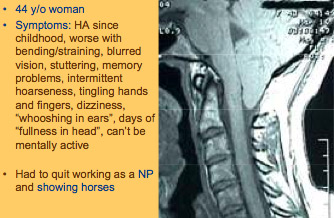

Figure 25

Here’s a 44 year old woman, [see Figure 25] she’s had headaches since childhood. They’re worse with bending, straining. She complains of blurred vision and stuttering, memory problems, intermittent hoarseness, tingling of the hands, dizziness, whooshing in her ears, fullness in her head and can’t be mentally active. She was advised to give up her nurse practitioner job. She did that, then she was advised that she had Chiari and that what she should do is give up her hobbies as well, which in her case was showing horses. At that point she took her life under her own hands and started trying to find out and learn about this. As you can see, a fairly pronounced herniation of the tonsils. In her case this is the preoperative and this is the postoperative with adding the graft. Not everyone does excellently. Let me repeat that and I’m sure we’ll talk about that throughout the meeting but she was obviously very pleased. Did not go back to nurse practitioning, but did not quit horse riding.

Figure 26

Here’s another, [see Figure 26] and this is just to point out, as Dr. Milhorat and others have pointed out, that up to about 1/4 of people with Chiari malformation, the symptoms will be trigger by a trauma and it doesn’t have to be a high speed motor vehicle collision. In this case it was a trampoline accident; this is when the extreme headaches began. Fatigue, distant looking eyes, heart palpitations, shooting pain, shortness of breath, poor sleep, anxiety, chest pain; a variety of symptoms. This is her obstruction in this area here, this is her postoperatively. Other than some occasional occipital pain, was doing quite well.

Figure 27

A young man, thick bone, [see Figure 27] sort of a boney anomaly if you will, very pointed, crowded tonsils. Here’s your foramen magnum- laughter almost causes him to pass out. These are some of the weightful centers – if you will – reticular activating centers – are in those areas that help control consciousness and he was probably impacting that area so tightly, feeling possibly loss of consciousness on that mechanism. Postoperatively this is what you’d like to see. [see Figure 28]

But on the other hand, let me say not everyone does well and there’s a lot of work to be done. Dr. Meuller and I, in the Neurosurgical Focus last year, published 112 patients whom we did an outcome study and I think you’ll hear more about that today, where they had a 6 or 8 page questionnaire before surgery and then a year after. We found 84% of people seemed to have very good outcome following this. Fortunately a lot of people can improve but not everyone. Now I think as you’ll also hear some of those people that did not improve also point to things like a back fusion surgery or other medical problems they had in that coming year. So it’s a little difficult to tease out exactly how people do following Chiari surgery and that’s going to be one, I think.

Figure 28

In our experience, to summarize, in our clinic we’ve focused quite a lot in keeping the complications as low as possible and I think we’ve been able to do that. I think the challenge, at least before us, and I think maybe others, is how can we better define who truly needs the operation and how can we improve our outcome? With that I thank you very much for the opportunity.

John Oró

Medical Director,

The Neurosurgery Center of Colorado

Founder Chiari Treatment Center

Aurora, Colorado